Helio Pires at Golden Trail recently wrote a post about local gods, specifically those of Alcobaça, Portugal. The post first looks into what evidence is available for deities historically worshiped in the locale of Alcobaça, then explores possibilities for finding a “local deity [or possibly a set of local deities] that stands out from the host of genii loci.”

I will utilize the same approach. There were a succession of Chinatowns in Santa Cruz, complete with temples, the primary deity of which appears to have been Guan Gong. All quotes are from local historian Sandy Lydon’s book Chinese Gold, unless otherwise specified.

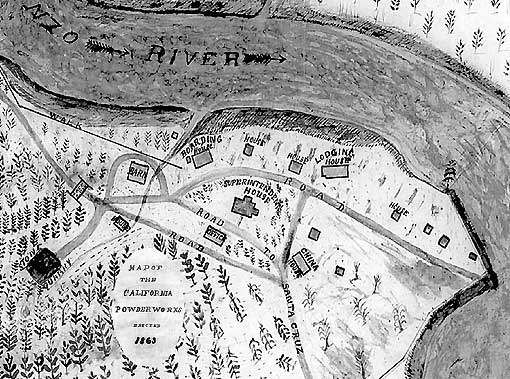

Powder Works: notice “China House” in the SE corner of the cluster of buildings

Powder Works: notice “China House” in the SE corner of the cluster of buildings

California Powder Works

The “first sizable group of Chinese” in Santa Cruz, who arrived in 1864, worked at the California Powder Works helping manufacture gunpowder (235). The temple at the powder works served the entire Chinese population of the Santa Cruz area:

From the mid-1860s to the mid-1870s more Chinese lived at the powder works than in the small Chinatown in Santa Cruz. The Santa Cruz Chinese would hire the Pacific Ocean House’s large carriage and join their fellow countrymen at the powder works to celebrate the lunar New Year and the June birthday of the primary god in their temple, Kuan Kung [Guan Gong]. The temple was probably the primary reason that the Santa Cruz Chinese traveled up to the powder mill to celebrate their holidays. (236).

The temple was maintained by the Chee Kong Tong, or the “Extend Justice Society,” which was an anti-Manchu secret society and benevolent association (266). Strangely, the Masons theorized that the Tong was a long-lost branch of the organization and dubbed them the “Chinese Freemasons.”

The members of the Tong adopted the label and associated imagery; I would speculate that doing so provided protection against the anti-Chinese movement. This led to the rare occasion where “Several times white Masons were allowed to witness rituals generally never seen by non-Chinese” (266).

In an even weirder twist of events, the site of the powder works is now the Paradise Park Masonic Club. Coincidence? Or a mix of sympathetic magic and feng shui? There is a major bend in the river there, as you can see from the map above, probably due to an outcropping of granite or some other hard rock…

Anyways, at the height of the anti-Chinese movement in 1878, the California Powder Works company fired all of its Chinese employees, of whom there were 35 in the early 1870s (226-7).

Willow Street/Pacific Avenue Chinatown

The Chinatown, Santa Cruz’s first, that was contemporaneous with the powder works Chinese population lasted from 1862 to 1877, and was located on what in 1862 was Willow Street. Willow Street was then a secondary street were rents “were probably quite low” (227). Lydon writes that “the Chinatown included a temple” (227) which we can surmise was used for observances that were smaller than New Year’s and Guan Gong’s birthday, but doesn’t specify what deity the temple was dedicated to.

In 1866, Willow Street was renamed Pacific Avenue and designated the main business street is today; rising rents drove the Chinese to move during the 1870s. The Chinatown, which included “a collection of laundries” (227), was between Walnut and Lincoln, where GAP now sells clothes “Made in China.”

Front and Pacific, between 1882 and 1892. Chinatown on left.

Front and Pacific, between 1882 and 1892. Chinatown on left.

Front Street Chinatown

The next Chinatown, which lasted from the late 1870s until 1894, was located on Front Street on the block where the Post Office and (currently closed) Vets’ Hall and Comerica Bank are now. River Street extension had not yet been constructed, so Chinatown extended to the intersection of Cooper and Front, and backed up to the San Lorenzo River: therefore “most of the buildings were up on stilts to prevent flooding” (232).

The Chee Kong Tong headquarters and temple were adjoined to the rear of Wong Kee’s grocery store, which had a gambling parlor and opium den on the second story (248). The temple was about where the Vets’ Hall is today, judging from a map on page 232. Ernest Otto describes the temple from his recollections of when he was present for a New Year’s ritual:

. . . in the center of the altar was an alcove for the picture of the gods, a group of several . . . the picture was a couple of feet back from the frame of the alcove of green with carved letters, with a touch of an oriental finish. Hanging from the center of the shrine was the ever burning light held in a brass holder. A pewter holder in front of the picture was filled with burning incense, punks or red candles made of grease. On each side of the alcove were tall, pewter holders for large decorated red candles and the tall punks.

A couple of feet in front was a table-like altar. On this was a large pewter bowl for the burning of the fragrant smelling sandal wood by the worshiper. The altar cloth hanging along the front was of brightly embroidered red silk on which were many circular mirrors.

Along the front was a piece of white matting on which the worshipper [sic] knelt and in his hand had the incenses and candles which were placed in the bowl. He would pour out libations of wine and burn paper representing the next world, money and clothes.

Lydon paraphrases Ernest Otto as estimating “that before the 1911 Revolution in China (which rendered some of the tong’s political purposes moot), 90% of the Chinese men in Santa Cruz belonged to the Chee Kong Tong; only the Chinese Christians did not join” (268). There were an estimated five hundred members in the greater Monterey Bay area (269). Initiations of small groups of men into the Tong were held in a room adjoining the temple. Of this small room, there are two descriptions. The first is from a group of white Masons who visited in 1883 just before an initiation, and was published in the Sentinel:

[…] a number of bowls were ranged on matting in which there were several kinds of meat, with cooked rice, thin strips of cocoanut and sweetmeats, the whole being placed before maps on which were depicted Chinese characters. Near these bowls were placed lights, and two large knives were crossed, and before the whole arrangement stood a number of Celestials chanting in a manner peculiar to themselves. (269).

Lydon relays that they left before the initiation, and “heard the door slammed and bolted behind us” (269). The second description is from Ernest Otto, who witnessed the initiation itself. He described an ever-burning candle in front of a small altar (presumably to Guan Gong), and further wrote:

There was also a circular steel rim and sword . . . [and] when the oath was taken the queue which was a sign of subjection to the Manchus, was unbraided, and the neophyte knelt with the circular hoop over him and the sword across his neck. (269)

In 1894, the Front Street Chinatown, including the temple, burned to the ground. Some people blamed Guan Gong for not better protecting Chinatown; one interesting piece of information, though, is that he was credited for past protection from proposed anti-Chinese legislation:

The Chinese mourn the loss of their Joss, blaming him for not protecting them from the fire. For years they have escaped, and the Joss was the recipient of much favor. When a move was made some years ago to make the Chinese go outside of the city-limits the Joss was given the credit of making the move a failure. As he was burned in the fire, the Celestials have no one to whom they can go for comfort. (280)

By the way, the etymology of the word “joss” comes from the “early 18th century: from Javanese dejos, from obsolete Portuguese deos, from Latin deus ‘god.'” And the term “Celestial” as referring to Chinese most likely comes from a translation of the phrase Tian chao (天朝) or “Celestial/Heavenly Dynasty,” which was “used by the Qing court to refer to itself in its own official documents” (Matthew Mosca, quoted from linked page).

The history of Chinatowns in Santa Cruz, as well as an examination of the cult of local earth god Tu Di Gong, will be continued in Part 2.

Source: Lydon, Sandy. Chinese Gold: The Chinese in the Monterey Bay Region. Capitola: Capitola Book Company, 1985.

Image Credits: Map of Powder Works village is from the Santa Cruz Public Library, as is the photograph of Front and Pacific.

April 10th, 2013 at 9:18 pm

Okay I have majorly fallen in love with this blog. Just letting you know.

Also, neat, another So Cal resident! (Unless Monterrey doesn’t count?)

April 10th, 2013 at 9:35 pm

Aww, thanks!

We think of ourselves as Central California, with a tendency to identify as Norcal rather than So Cal. But it’s all Cali, right? At least until an earthquake splits it in two… 🙂

April 10th, 2013 at 10:55 pm

[…] The Heathen Chinese blog posted an incredibly detailed, two part piece on local Chinese Gods in the Santa Cruz area. This Santa Cruz area writer focuses on Chinese Polytheism and history of the worship of these deities. Part one: https://heathenchinese.wordpress.com/2013/04/10/local-gods-part-1/ […]