ADDENDUM: The Chinese Gods of Wealth website is insistent that the most common Chinese God of Wealth, the one who holds the appelation of “Cai Shen,” is Cai Bo Xing Jun (财帛星君), who was a magistrate of the Northern Wei Dynasty named Li Gui Zu (李诡祖). That website identifies Zhao Gong Ming as one of the five wealth gods corresponding to the cardinal directions, with Zhao Gong Ming occupying the Central direction.

The website says that while the 5th day of the 1st lunar month is a day to pray to all wealth gods, the 15th of the 3rd lunar month is the specific celebration date for Zhao Gong Ming. Zhao Gong Ming is also considered the “Military God of Wealth,” as opposed to several deities who are Civil Gods of Wealth (including Cai Bo Xing Jun, Bi Gan, and Fan Li).

I just San Francisco’s Chinatown, and I did indeed see separate statues for Cai Shen and Zhao Gongming, so I think that the Encyclopædia Brittanica is mistaken.

Original Post: One of a number of Chinese gods known to bestow wealth is Cai Shen (財神 – literally, “wealth god”). As discussed with Tu Di Gong, this title appears to be a position in the celestial hierarchy that can be filled by different individuals. The Encyclopædia Brittanica entry on Cai Shen lists two possible occupants of the position, and tells a very interesting story about the first:

The Ming-dynasty novel Fengshen Yanyi relates that when a hermit, Zhao Gongming, employed magic to support the collapsing Shang dynasty (12th century bce), Jiang Ziya, a supporter of the subsequent Zhou-dynasty clan, made a straw effigy of Zhao and, after 20 days of incantations, shot an arrow made of peach-tree wood through the heart of the image. At that moment Zhao became ill and died.

Later, during a visit to the temple of Yuan Shi, Jiang was rebuked for causing the death of a virtuous man. He carried the corpse, as ordered, into the temple, apologized for his misdeed, extolled Zhao’s virtues, and in the name of that god canonized Zhao as Caishen, god of wealth, and proclaimed him president of the Ministry of Wealth. (Some accounts reverse the dynastic loyalties of Zhao and Jiang.)

Another account identifies Caishen as Bi Gan, put to death by order of Zhou Xin, the last Shang emperor, who was enraged that a relative should criticize his dissolute life. Zhou is said to have exclaimed that he now had a chance to verify the rumour that every sage has seven openings in his heart.

There are a few things to consider aside from the fascinating example of Chinese malevolent sorcery/curses (it’s quite a process!). For one, both stories would place the origin of the wealth god(s) at the end of the Shang dynasty, over 3000 years ago.

For another, the dynastic loyalties are ultimately not that important. I don’t know what accounts reverse their loyalties, Jiang Ziya is the main character in Fengshen Yanyi and is clearly against the Shang Dynasty and in favor of the Zhou. However, the story of Zhao Gong Ming suggests that even if one is on the wrong side of the “Mandate of Heaven,” one deserves respect for one’s virtue and integrity.

What has always struck me about this story, though, is that Zhao Gong Ming is described as a “hermit.” That seems to be almost the opposite of a god of worldly wealth, and yet that’s what he ends up becoming

Then again, as the novel describes literally scene after scene of magical warfare, it seems like one had to be a practitioner of sorcery to be a character worth mentioning in the story, and recluses in the mountains would be the typical possessors of those skills.

Furthermore, a total of 365 gods are appointed from the slain at the end of the novel, so at that point there were probably bound to be some matches that didn’t make the most apparent sense.

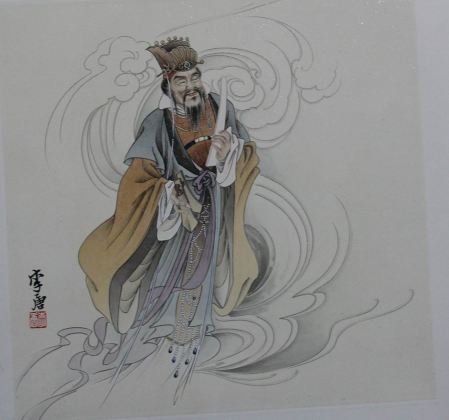

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, where the statue shown above resides, discusses the origin of Zhao Gong Ming: “The figure probably represents the Heavenly Marshal Zhao (Zhao Gong Ming), a popular local god of wealth who was absorbed into the Daoist pantheon.” Notice that they translate “Gong Ming” as a title: I’m not sure if this is the only way to understand the name, but I will look into it.

Another thing the MMA’s short description brought up was the thought that probably all gods began as local gods, even if they arose in the context of a centralized empire and their cultus rapidly spread throughout that empire. It may be a little redundant to draw attention to this fact, if that is indeed the case, but it hadn’t really crossed my mind previously.

Wan Pin Pin’s 1987 dissertation on Investiture of the Gods says that the novel may have been written in the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368) rather than the Ming and by a different author than traditionally assumed (2-3). Be that as it may, the part of the dissertation that concerns me right now is the appendix, where Wan provides a chapter-by-chapter summary.

First, it must be noted that in the opening chapter of the novel, the king blasphemes Nu Wa while in her temple, she divines that his dynasty was already predestined to fall in 28 years, and she sends a fox demon and two other demons to “seduce him and confuse his mind, but not harm the people” (437).

Chapter 46 is where Zhao Gong Ming makes his entrance, as he is recruited to the cause of the Shang Dynasty. On his way to the battlefield, “Zhao subdued a black tiger and rode it” (480). Many contemporary statues of Zhao Gong Ming depict him riding a tiger:

Chapter 47’s summary describes Zhao Gong Ming using a “magic whip” as well as a magic “Sea Pacifying Pearl” (480); according to a different but less reliable source, his weapon is a “lightning staff” and he possesses 24 of the pearls, which force “all foes present to their knees in blindness.” At one point, he loses both the whip (staff) and the pearl(s) as a result of running afoul of “two Taoists playing chess [or Go, weiqi in Chinese]” (481).

He then has to borrow the “Dragon Scissors” from his sisters, which “were transformed from two dragons and had the power to cut any immortal body into pieces” (481) That’s when Jiang Ziya, with the aid of another hermit named Lu Ya, uses magic to kill Zhao Gong Ming:

A Taoist Lu Ya came to visit, saying that he came to subdue Zhao Gong ming. He told Ziya to build an altar and bond a straw man with Zhao’s name written on it. He wrote charms on a book and set one lamp on the head of the straw man and one at the end of his feet. Ziya chanted the spell and exercised the magic accordingly. After three days or so, Zhao became restless and uneasy. […] After Ziya had exercised his magic for twenty days, Lu Ya came to see him. Lu brought with him a small peach wood bow and three peach-wood arrows; he told Ziya to use it at noon on the twenty-first day. When the time came, Ziya first shot at the left eye of the straw man, then the right eye, and finally at the heart. In Wen’s camp Zhao died at noon, with blood flowing from his two eyes and heart. (481)

Zhao Gong Ming’s sisters, whom he borrowed the Dragon Scissors from, are described as “fairies” and they set out to avenge his death, but prove unsuccessful as Laozi himself intervenes (482).

In Chapter 99, Jiang Ziya and the new Zhou Dynasty have won the war, and Yuan Shi decrees that 365 gods would be “canonized” from the “souls and spirits” of the slain, divided into “eight departments,” each one “in charge of one aspect of the human world” (516). Wan’s summary doesn’t mention Zhao Gong Ming by name, but presumably the novel does at this point. This scene is also where the title of the novel comes from.

Yuan Shi, or Yuan Shi Tian Zun, is one of the “Three Pure Ones” or supreme deities of Daoism. Deng Ming-Dao, in The Lunar Tao, translates his name as “Heavenly Lord of the Primal Origin” and describes how “he set the stars and planets into motion and was the main god until he retired and the Jade Emperor […] became the celestial ruler” (12). Deng Ming-Dao also says that Yuan Shi is ” a personification of […] the abstract notion of an impersonal and mysterious beginning to all things” (12).

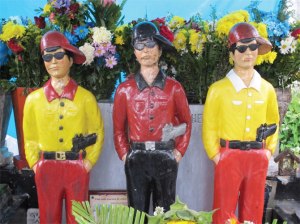

The Lunar Tao also contains a photograph of the Changchun Temple in Wuhan, where Guan Gong, Zhao Gong Ming and Bi Gan stand side-by-side on an altar to the Gods of Wealth (9), thus proving that the Encyclopædia Brittanica is correct to identify both Zhao Gong Ming and Bi Gan as gods of wealth, but hasty in implying that one or the other must be “Cai Shen.” Deng Ming-Dao states plainly, “there are several different gods of wealth” (9).

He also reminds us:

The God of Wealth doesn’t merely dole out riches. While people make offerings to him in their homes, and businesspeople keep him in their stores, everyone still has to work. Great wealth is earned.

To be wealthy, we have to work hard and we have to be smart. The God of Wealth may accept the offerings on the altar, inhale the incense, and thrill to the firecrackers, but the real offering he requires is hard work. (9)

Hard work can apply to many different paths, from a reclusive hermit practicing sorcery in the mountains, to a warrior defending what they believe in, to a homesteader creating true wealth by working with the land.