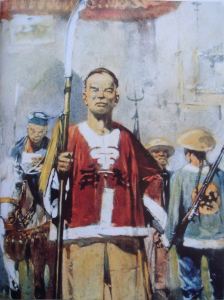

Guan Yu Mural at Summer Palace, Beijing. Credit: Shizhao.

San Guo Yan Yi (三国演义, Romance of the Three Kingdoms) is one of China’s Four Great Classical Novels. It is a historical novel dealing with the Three Kingdoms period (220-280 CE) and is based upon Chen Shou’s Records of the Three Kingdoms (Sanguozhi, 三国志), which was written in the late 3rd Century CE.

Romance of the Three Kingdoms is traditionally said to have been authored by Luo Guanzhong. Brian May, Takako Tomoda and Michael Wang question this attribution in an essay on the physician Hua Tuo (who is featured as a character in the novel):

Little is known about Luo but he appears to have been a poet and recluse who lived during the last years of the Yuan [Mongol] dynasty. He was probably born between 1315 and 1318 and was still alive in 1364. One source suggests that he was involved in anti-Yuan rebellions in south China but retired to write an unofficial history (Roberts 1995).

Although Luo is given as the author, he could not have written the version of the Romance that we have today. The earliest extant version of the Romance is prefaced 1494 and the earliest edition is dated 1522. However, modern versions are based on the Mao edition that appeared in the mid 1660s (Roberts 1995).

Consequently, the Romance must be considered a product of the Ming Dynasty that is based on earlier historical and popular works that may included one by Luo. Even though the Romance is the least reliable source for the Hua Tuo story, the popularity of this novel makes it the most influential. (2-3)

Though May, Tomoda and Wang are writing about Hua Tuo, the last sentence can be applied with equal accuracy to Guan Yu (the historical figure later deified as Guan Di).

Obviously, as a historical novel written over a millennium after the events it covers, the Romance cannot be considered a reliable historical source for the Three Kingdoms period: that would be Chen Shou’s work. On the other hand, it does provide some insight into the popular stories being told during the time period in which it was written.

As Sannion at The House of Vines wrote recently, there are many different types of “religious literature.” To use his examples, the Romance should be seen as closer in intent to the writings attributed to Homer than those attributed to Orpheus. The analogy doesn’t hold up under closer scrutiny, of course, since the Romance is actually a novel taking great liberties with the writings of a historian (Sannion’s first category, for which he provides Diodorus Sikeliotes as an example).

In “From History to Fiction: The Popular Image of Kuan¹ Yu,” Winston L.Y. Yang argues that with regards to the character of Guan Yu, the Romance actually “adhered fairly closely” to the source material:

Many episodes historically unfounded and obviously created by Luo Guanzhong or borrowed from popular legends have led scholars to believe that Guan has been portrayed in the novel essentially as a man of dignity, righteousness, extreme nobility, and superhuman bravery. […]

Roy Andrew Miller believes that the fictional Guan Yu has completely replaced the historical one in the Chinese imagination. But there are many other episodes in the novel which show that Luo has adhered fairly closely to the image of Guan projected by Chen Shou in his official history. (71)

After providing some examples of negative traits that Chen Shou attributes to Guan Yu that also find their way into the novel, Yang argues that the Romance was not intended as a hagiography (which it wasn’t, as far as I can tell); however, Yang goes on to say that any and all stories about Guan’s deification were merely a “concession to popular taste” (79).

It should be understood, however, that Luo, influenced by popular literature and writing at a time when Guan had already become an object of national veneration and worship, could not but take the national sentiment into consideration and accord the hero all the glorification which has been heaped upon him in popular legends and myths.

Thus, Luo has created numerous details pertaining to Guan’s extraordinary bravery, loyalty, and nobility of character, in line with the popular image of the hero. But only occasionally does he make Guan appear a saint or god, as demanded by the popular beliefs of his time. Yet, on the other hand, Luo follows closely the official history of the San Guo period, San Guo Zhi, his most important source. (78-9)

Yang’s argument here is highly debatable (he confuses “deification” with “portrayal as a perfect human being,” when the two are not the same thing), but that is not the point of this post, which is instead to present precisely those stories about Guan’s apotheosis. Without further caveat or disclaimer, then…

Guan Di Statue at Jinguashi, Taiwan. Credit: Fred Hsu.

The following quotations are from the highly abridged version of Moss Roberts’s translation. Guan Yu is executed by the ruler of Wu, Sun Quan. Later, at a banquet, Sun Quan presents his general Lü Meng with a cup of wine:

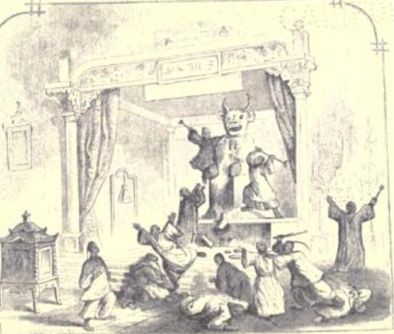

Sun Quan personally poured the ceremonial wine and presented it to Lü Meng. Receiving it, Lü was about to drink when he dashed the cup to the ground and seized Sun Quan with one hand. “Blue-eyed boy!² Red-whiskered rodent! Have you forgotten me? Or not?” The assemblage was aghast.

As someone moved to stop him, Meng knocked Sun Quan to the ground and with long strides came to the throne and seated himself upon it. His eyebrows arched vertically, his eyes grew round and prominent as he bellowed: “I have crisscrossed the empire for thirty-odd years since defeating the Yellow Scarves, only to have your treacherous trap sprung on me. But if I have failed to taste your flesh in life, I shall give your soul no peace in death—for I am Lord Guan Yü, master of the Han Shou district!”

Fear-stricken, Sun Quan led the assemblage in offering obeisance. Lü Meng collapsed on the ground, blood ran out of his seven orifices, and he died. There was general terror, and thereafter Sun Quan was tormented with fear over the execution of Lord Guan. (244)

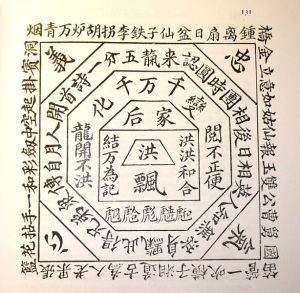

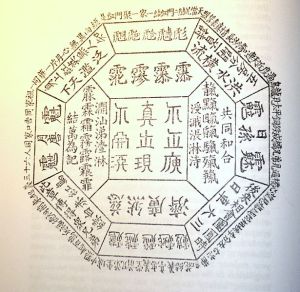

Possession and death by bleeding from one’s orifices are also featured in the Guan Di World-Subduing, Eternally-Effective, Disaster-Relieving Prayer.

Sun Quan then sends Guan’s severed head to Cao Cao, ruler of Wei, in an attempt to shift blame for Guan’s execution to Cao Cao:

The wooden box was presented. Cao Cao opened it and saw Lord Guan’s face, just as it had been in life. Cao smiled. “You have been well, I trust, general, since we parted?”³ Before Cao could finish, the mouth opened, the eyes moved, and the hair and beard stood up like quills. Cao fell in a faint, reviving only after a long spell. He said to his officers: “General Guan is no mortal.”

The messenger from the South told him how Lord Guan’s powers had entered into Lü Meng and reviled Sun Quan. This increased Cao’s fear. He adopted Sima Yi’s advice and buried the head and a wooden corpse with full royal honors outside the south gate of Lo Yang. All the officers and officials were told to tend the body, while Cao personally made offerings. (246)

These particular stories might be nowhere to be found in Chen Shou’s Records of the Three Kingdoms, but they do give us an idea of Ming Dynasty-era stories being told about the power of the god Guan Di.

Endnotes:

¹All subsequent Chinese transliterations have been rendered in Pinyin rather than Wade-Giles.

²The word used is bi 碧, which means “emerald” and can signify either blue or green. Chen Shou’s Records of the Three Kingdoms reports that Sun Quan’s eyes were said to be jing guang 精光. 光 means “light.” 精 is a word that can mean “energy” or “spirit” (in the sense of energy, not of a ghost) or “semen,” but originally meant “crystal.” See this post for more on jing.

Chen Shou says nothing about Sun Quan’s hair. Another translation of this passage (Yang 74) translates “You green-eyed boy! You purple-bearded rat!” It is also worth noting that Guan Yu’s liege lord is described as having arms that reach past his knees and earlobes that reach his shoulders…

³A line Cao Cao had used before to convince Guan Yu to spare his life; Cao Cao had once taken Guan Yu prisoner and spared him, and this line was used to remind Guan Yu of that fact.