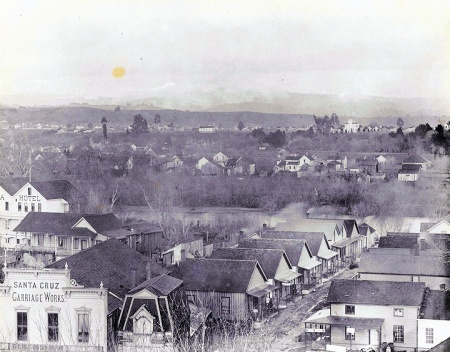

1894-1955 Chinatown. Photo taken c. 1900, temple wasn’t moved yet.

1894-1955 Chinatown. Photo taken c. 1900, temple wasn’t moved yet.

After the 1894 fire, there were two separate Chinatowns established: one was “located a hundred yards downstream” on an island, called the Midway, in the San Lorenzo River (281), and the other was on south Chestnut Street in the vicinity of Neary’s Lagoon. The group that moved to Midway was larger and “predominantly Christian” (433). From what I can see of maps and photographs (such as the one above), Midway did not remain an island when the river was low, but as stories attest, it was extremely vulnerable to flooding.

The Chee Kong Tong temple was rebuilt at the Chestnut Street Chinatown (434), which is now the location of apartment complexes. In 1905, the Southern Pacific Railroad bought twenty acres west of Chestnut with the intention of constructing a railyard. They demolished all of the Chinatown buildings, despite offers to buy the buildings intact by real estate developers, except for the Chee Kong Tong temple and headquarters which were disassembled and moved to the other Chinatown, which was located where the Galleria and Riverfront movie theater are today.

Chinatown, temple not in view. 1940s.

Chinatown, temple not in view. 1940s.

The temple was set up right next to the river on the eastern end of Chinatown, and it was oriented to face the river (or perhaps the direction East). Lydon describes the dedication celebration, at which over 50 Tong members participated, quoting from the Surf, the arch-rival of the Sentinel:

Each brought his offering of punks and Chinese candles and then kow towed before the joss with burning punk in hand, offered his libation of wine, pouring it on the floor, while bowing, and then burned his lucky paper representing cash, while outside firecrackers were discharged. (437-8)

Lydon goes on to summarize other features of the dedication celebration:

Two roast pigs were laid on the altar, and the air was filled with incense smoke. A large banquet followed […] The place of honor on the altar was occupied by an image of Kuan Kung [Guan Gong], and he was surrounded by “red banners, and tablets of green.” (438)

As the 1900s progressed, the Chinese population of Santa Cruz dwindled. With the decline in population, the temple was increasingly neglected as well. In 1930, the Sentinel reported on sad state of the Chinese New Year’s celebration, usually the high point of the year:

The Chee Kong Tong joss house is practically deserted. Several of the old timer visit to worship, but none of the younger men are seen there . . . The [private] dinners are as elaborate as ever, but with none of the old time music of drum, cymbal and gong. The Santa Cruz orchestra was always a three piece affair. The instruments are in the joss house, but untouched. No stores have the elaborate shrines in the front room with silk hangings, large banners and the many Chinese lillies [anymore]. (442)

The temple figures in one last story: Chinatown was prone to flooding, and “residents […] usually responded to floods by moving their belongings upstairs to the second story. In 1940 three elderly residents were rescued from the balcony of the temple” (443). The temple was dismantled in 1950. The last Chinese family, the Lees, left after the Christmas flood of 1955 and the remaining buildings were demolished shortly thereafter.

Tu Di Gong

So, we’ve established that Guan Gong was the major deity of the Chinese population in Santa Cruz in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Then there is the question of local gods. For most places in China, this would be a simple question: the local Tu Di Gong serves precisely that function. “Tu di” (土地) means “earth,” while “gong” (公) means “duke” or “official” and is a common title for deities (such as Guan Gong).

According to Christopher A. Hall in his article “Tudi Gong in Taiwan, Tu Di Gong can be depicted in diverse forms, from ornate figurines to simple stones:

Tudi Gong shrines can range from small, informal stone boxes standing alone in fields or near sidewalks, to stalls in temples dedicated to other gods, to grand temples specifcally for Tudi Gong on the scale of those for more powerful gods. Typically the most humble shrine contains a picture, calligraphy of Tudi Gong’s name, or a small stone statuette and an incense pot.

Near a gravesite the shrine may be as simple as a stone with the characters for Houtu carved into it. But often the Houtu stone is more elaborate: intricately carved, perhaps, with paint and other pigments applied. (107)

Under tree, Tian Hou Temple, Shenzhen

Under tree, Tian Hou Temple, Shenzhen

Hall writes that the moniker “Tu Di Gong” can be thought of as “an appointed position represented by a different individual from place to place and time to time,” often filled by “a person who, in life, was a good person” (97). The government of the Republic of China (Taiwan) has a slightly different characterization of Tu Di Gong:

According to the Government Information Office (2008), Tudi Gong is “a single deity in essence” who “nevertheless has myriad spirit avatars whose mission is to look after local tracts of land and the people on them.” (100)

Fascinatingly, though many Taiwanese believe in the theory that Tu Di Gong is a position filled by mortals who have attained apotheosis, the individual identity of the local Tu Di Gong is not actually known:

a story of a historical man should lie behind each Tudi Gong. I was told that there is; but I was also told that no one knows the stories. When asked, “Who is this Tudi Gong?”—with the understanding of the metaphor [of an imperial position being filled], my respondents all said that they did not know. (110)

Hall recorded a singular instance, filtered through several layers of hearsay, where the identity of a new Tu Di Gong was revealed:

a Tudi Gong had come to a person […] in a dream. The Tudi Gong told the dreamer that he, the Tudi Gong, had been promoted. The Tudi Gong informed the dreaming man that the community needed to begin worshipping such-and-such a person as the new Tudi Gong of that place. That was the extent of the story. According to my informant, the [storyteller] remembered neither where this oneiric event took place nor who the old and new Tudi Gongs were. (110)

The area of responsibility of a specific Tu Di Gong can be quite small: according to some of the Taiwanese Hall interviewed, “Even if one is across the street from another, the two will be different Tudi Gongs” (111). Hall reported the burning of incense to Tu Di Gong to be bimonthly, occurring on “the first and fifteenth for most but the second and sixteenth for merchants” (104).

Next to grave near Meilin Park, Shenzhen

Next to grave near Meilin Park, Shenzhen

Tu Di Gong in the Monterey Bay Area

The rest of Hall’s article is a worthwhile read. We turn now, though, to evidence of Tu Di Gong’s worship in Central California. Sandy Lydon writes that an annual celebration was held in Tu Di Gong’s honor on the second day of the second lunar month at the Point Alones fishing village on the Monterey peninsula: ” Beginning in 1894, and each year thereafter until 1906, Chinese, like pilgrims to Mecca, came from throughout the Monterey Bay Region […] to participate” (322).

The highlight of the festival was a Chinese custom that came to be known as the Ring Game, wherein a ring of woven bamboo was projected into the air by a giant firecracker, and the participants (divided into teams by town of origin) would scramble to capture the ring. The man that succeeded in winning the game “brought luck to himself and honor to his teammates” for the rest of the year (323).

The game had its perils as well: “In 1899 one of the bombs exploded prematurely, injuring the eye of the ordnance expert, and in 1900 one Chinese participant died from injuries suffered during the scramble ” (326). Regardless of danger, the festival was a major event:

The contests […] in 1899 and 1900 attracted the largest crowds, with Chinese delegations coming from San Jose, Gilroy, Salinas, Watsonville, and Santa Cruz. The expense […] in 1899 was estimated in excess of five thousand dollars [that’s 1899 dollars!] and the hundreds of Chinese participants were observed by over two thousand white onlookers. (326-7).

White onlookers tend to cause problems: “The games were often interrupted by whites who insisted upon joining the scramble” (326). Whites often vandalized personal property in the village (345-6), and invaded privacy to the point where a group trying to spy on a family eating a meal moved from window to window until all of the curtains were drawn! Lydon writes:

A witness correctly observed that, to the onlookers, the desire of the Chinese family to eat in private “was of no consequence–they were only ‘heathen Chinese.'” (346)

Beginning in 1898, the participants embarked on a mile-long parade from the Monterey train depot to Point Alones. In 1899, the Watsonville parade delegation was two hundred strong and included lion dancers, the altar from Watsonville’s Chee Kong Tong temple, men carrying spears and pikes, costumed women on horseback, and more. Lydon writes:

Appropriately, the Watsonville delegation again won most of the rings that day. Apparently, T’u Ti [Tu Di Gong] was impressed with all the preparations that the Watsonville Chinese had undertaken in his honor.” (329)

The Point Alones village burned in 1906, after which the celebration was moved to the McAbee Beach Chinatown next to Cannery Row. However, after the move “it lost momentum, and the final Ring Game was played in the 1920s” (329).

Clearly, Tu Di Gong had a presence in this area, and a pretty big one as well!

Here is another altar without anthropomorphic representation:

Tablet with two stones,

Tablet with two stones,

Cheung Chau Island, Hong Kong

Sources: Hall, Christopher A. “Tudi Gong in Taiwan.” Southeast Review of Asian Studies 2009: 97-112. Web.

Lydon, Sandy. Chinese Gold: The Chinese in the Monterey Bay Region. Capitola: Capitola Book Company, 1985.

Image Credits: The c.1900 photograph is in UCSC Special Collections and reprinted in various places. The scan used here is from Bratton Online even though the information below it is incorrect: it had the best contrast.

The 1940s photograph is by George Lee, retrieved from Santa Cruz Patch.

Photographs of Tu Di altars are by the Temple Guy. Note the different forms the altars take. Here’s one more:

Stone platform, Hong Kong. There are two stones in the back.

Leave a comment